Web Fonts and the Critical Path

Posted on | Comments

his blog corresponds to my May 2013 talk @frontendlondon. The slides for that talk can be found on slideshare.

The story behind FOUT

CSS is justified critical due to the flash of unstyled content which would ensue if we deferred it. This is the main reason why web fonts are deemed critical to web pages: to avoid the flash of unstyled text which is then later repainted.

When font-face landed we had this new tool at our disposal. It was shiny, fancy and it brought with it its own challenges: namely that in certain browsers there would be a flash of the fallback font until the browser had finished downloading the resource. We had a problem and, as front end developers love to do, we set about to race to be the fastest to fix it.

Somewhere along that path it became a best practice to place web fonts on the critical path. If your site had a Flash of Unstyled Text it was considered a poor implementation of font-face. It still is, for that matter.

But how critical are web fonts?

How often do we stop to reconsider our best practices? We solve a problem but does it really benefit our users? Let's talk about first world problems:

You're on the london underground (we have free wifi at stations now) and you come across a link on twitter which looks interesting as you're rocketing through the tunnel. You know that when you get to the station you have about 45 seconds to connect to the wifi, to hit the link, and for the content to load before you're plunged back into the tunnel; instead you get a white screen because the site has put a 50k font on the critical path and you never get to read the content. At this point are web fonts critical to you as a user? Or would you have preferred the content straight up?

Another example, and one closer to home for me and the team at Lonely Planet, is that of internet cafes. You might be in Thailand trying to book a boat, transfer money, find a place to stay that night, and you're sitting in an internet cafe sharing one DSL line with 50 other kids all playing online multiplayer games. You're staring at white screens and invisible text. We're forcing a design luxury on a user who just wants the content.

And those are just the first world problems.

The browser and the spec

I always advocate leveraging the browser to do the heavy lifting for you and we always try to avoid reimplementing browser features. This should be sound advice for most web developers. That said, you don't always have to agree with browsers and their implementation.

With web fonts, browsers are forced to make a decision from two distinct options: block the render or repaint later. The spec leaves it wide open for implementation:

…user agents may render text as it would be rendered if downloadable font resources are not available or they may render text transparently with fallback fonts to avoid a flash of text using a fallback font.

In cases where the font download fails user agents must display text: leaving transparent text is considered non-conformant behavior.

As you would imagine, from a wide open spec like this, implementation is very varied:

| IE | Firefox | Webkit |

|---|---|---|

Text rendered immediately then repainted later. | Invisible Text with a 3s Timeout | Invisible Text with no Timeout |

Edit 12 January 2015

Since Chrome moved to Blink they adopted the Firefox model.

Out of these, webkit is the only current implementation which is non-conformant. Firefox tries to hedge their bets with a clever timeout implementation but 3s is still a somewhat arbitrary number which is easily hit if you throttle your bandwidth even slightly. When that happens you're hitting your users twice as hard with slower perceived speed and a flash of unstyled text. But at least the users will see the content eventually…

Webkit have been working on the timeout issue and how best to calculate where that threshold should fall. This is good progress but, as you can see from the below dates, we're now four years into a decision:

https://bugs.webkit.org/show_bug.cgi?id=25207 ~ 2009 https://code.google.com/p/chromium/issues/detail?id=235303 ~ 2013

This may say more about the challenge than it does about priorities. There isn't a correct answer that will satisfy all users: invisible text is considered a feature and a bug to many.

Alright I get it, but I still want to have fonts on my site.

So do I. Web fonts can look fantastic and should still be embraced as a great feature. What we need to work on is minimising their impact on the speed of the web.

Trimming the fat

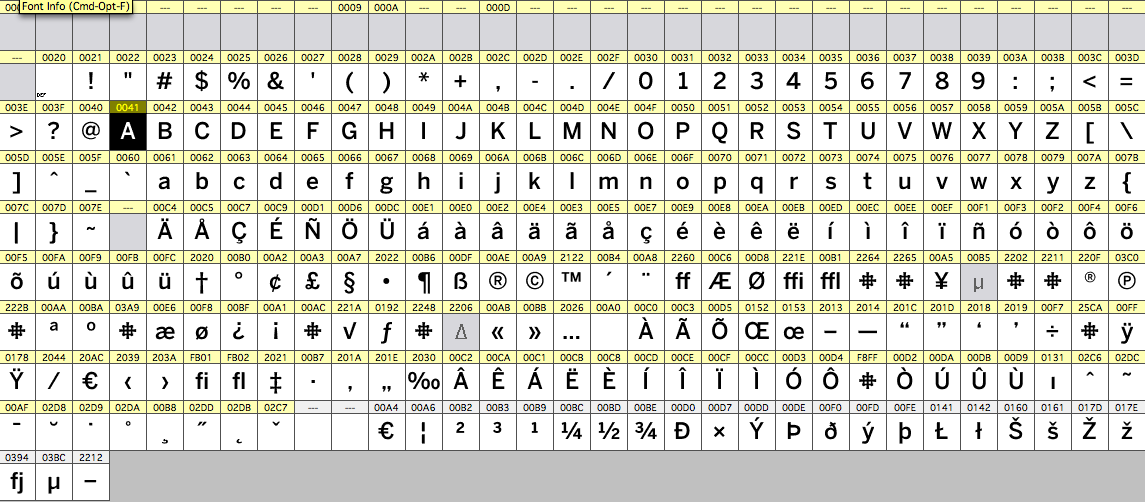

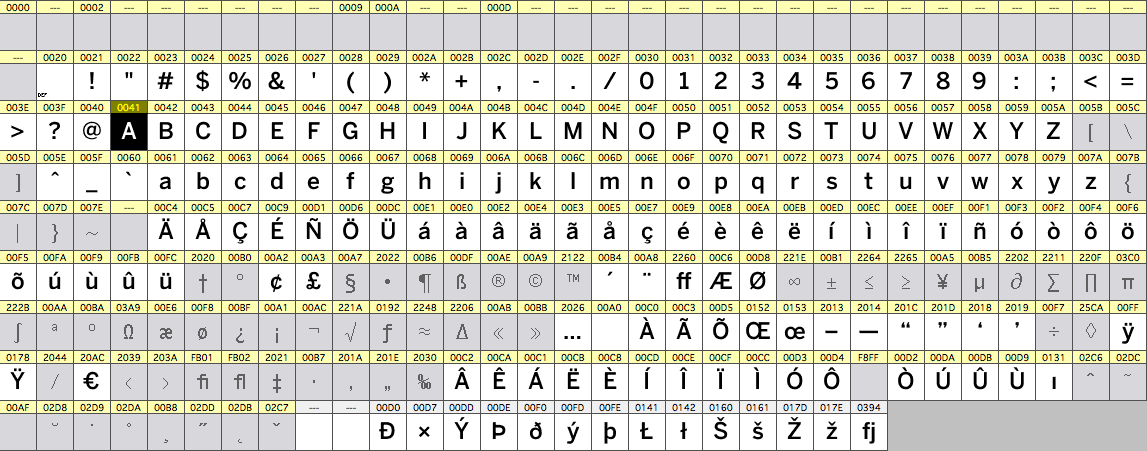

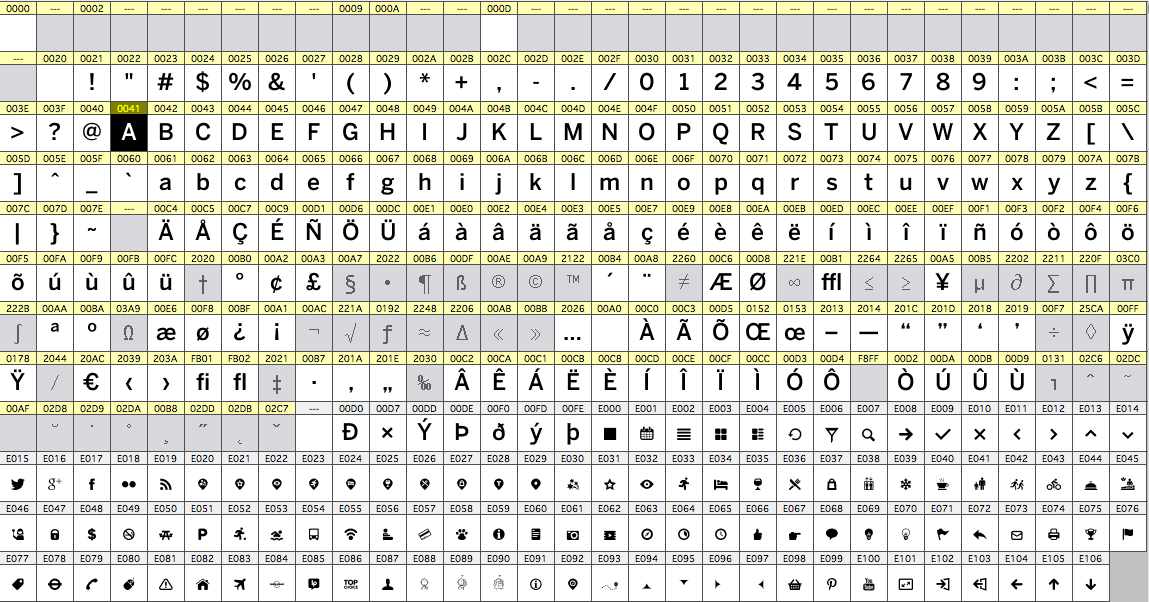

Before you even have to think about font loading techniques you should first look at reducing the weight of the font by subsetting. This is the practice of removing superflous glyphs that you serve within the font. For example, we remove all the mathematical glyphs and accept that if they are required they will be served by the next font down in the stack. They will look different to their surrounding glyphs, if requested, but this is an edge case we are happy to deal with.

The savings for this kind of bespoke pruning will usually be fairly small. That said, if you are using an extended font and only serving characters in one language, there could be some really significant savings.

LP font before and after:

There is an open source program called FontForge (archaic but powerful) which can be used to achieve this, as well as commercial programs such as TypeTool, Glyphs and Glyphs mini.

It's worth mentioning that there are generally legal requirements surrounding the modification of font files. Ensure that you check the terms and conditions of whichever foundry you are using before doing so.

Making the font work harder

If you have a design that requires heavy typography and liberal use of icons you might find performance optimisations in bundling the two together. Using one of the above programs you would be able to load your icons in vector format and place them in the private unicode area of your font.

By doing this you create a library of scalable, retina ready icons without the need for any extra requests.

The only downside to this approach I have found is it handcuffs you into coupling the same level of importance to your fonts as to your icons. If you decided that you wanted to progressively load your font after the page, the icons would come along for the ride.

Font Loading solutions

If you're loading web fonts via a third party using JS you should be loading it asynchronously. This should really be a default setting as otherwise you're creating a SPOF for your site. I would highly reccommend looking into the Google Web Font Loader and taking a look at these great slides by Richard Rutter on the subject.

If you're self hosting there are a number of techniques available to your. Below are five different methods, the first two place the font on the critical path and block the rendering of the page whilst the latter ones showcase our options for deferring the font load.

1. Synchronous, external

@font-face {

font-family: 'MyWebFont';

src: url('webfont.eot'); /* IE9 Compat Modes */

src: url('webfont.eot?#iefix') format('embedded-opentype'), /* IE6-IE8 */

url('webfont.woff') format('woff'), /* Modern Browsers */

url('webfont.ttf') format('truetype'), /* Safari, Android, iOS */

url('webfont.svg#svgFontName') format('svg'); /* Legacy iOS */

}

This is your typical font-face loading technique. In this case you hand all the control to the browser and allow it to load the font using whichever technique they implement.

This example code is outputted by the FontSquirrel generator which is an invaluable tool for handling fonts cross-browser.

2. Synchronous, Inline

The support for .woff font files is approaching 100% these days, with only IE < 9 (.eot) and old Android (.ttf) requiring others.

Given that, and the ability to base64 encode woff files, we are capable of serving fonts inline to the majority of our users. Doing this means we can reduce the number of requests one further by combining the font with our css. This can be a serious win if latency is an issue for your users, but it comes with a couple of caveats:

Caching

If you're deploying new revisions to your css regularly you're going to be constantly causing your users to re-download an unchanged font. Not cool. To get around this you can split your css into two: rarely changed and often changed. For example you could bundle your font with your reset, your base styles, your abstractions and your header and footer styles which are likely to also remain unchanged.Slower perceived speed

The big downside to the inline approach is you block the render of the entire chrome, not just the type you have styled. The user will see nothing but a white screen until the single asset has downloaded at which point the complete page will be rendered. Depending upon the latency of your users this approach can still end up painting to the screen faster than other approaches. You should probably avoid this technique if you are using web fonts in just a few places on your site.

The most important part of using this approach is ensuring that you don't serve the woff to browsers that can't render it. If your users are browsing your site on old version of Internet Explorer then the chances are they're not too happy about it already; don't punish them further by forcing them to download 30k + of assets they can't use. You can handle this by using IE conditionals.

<!--[if (gt IE 8) | (IEMobile)]><!-->

<link href="common_core_with_base64.css" media="all" rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" />

<!--<![endif]-->

<!--[if (lt IE 9) & (!IEMobile)]>

<link href="common_core_without_base64.css" media="all" rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" />

<![endif]-->

3. Simple Asynchronous Loading

var f, x;

x = document.getElementsByTagName("script")[0];

f = window.document.createElement("link");

f.rel = "stylesheet";

f.href = "#{asset_path("woff.css")}";

window.setTimeout(function(){

x.parentNode.insertBefore(f, x);

},0)

This is the classic asynchronous script loader modified to be a stylesheet loader. With this approach you are guaranteeing a FOUT on the first load but on subsequent loads the font will be cached and there will be no FOUT.

This is the simplest way of taking the font off the critical path. In order to make this technique work well and minimise the impact of the repaint you need to ensure that you adjust the typographic treatment of the fallback font to closely match the web font. In order to do this you might want to add a class to the body after the font has loaded which you use to update the type treatment. This is a similar approach to how Google Web Font Loader works.

4. Asynchronous Loading with Local Storage

A similar approach to the one before, but one worth mentioning, is substituting Local Storage for the browser cache. This is a technique currently used by the Guardian on their responsive site and is validated by the theory that they can't always trust the http cache on mobile to be available to them.

Essentially the technique is to check to see if the font is in Local Storage on load and, if so, inlcude it in the head in order to avoid any repaint. If it isn't available in the cache then the font is loaded asynchronously and stored in Local Storage after checking whether or not there is enough free space. The type on the page is then repainted.

The only downside to this approach is the time taken to access Local Storage (minimal) and the fact that you are having to re-implement a browser feature. Still, it is a technique worth investigating if you have similar concerns.

5. Async & Defer

This is a neat solution proposed by Chris Coyier in his article on css-tricks (http://css-tricks.com/preventing-the-performance-hit-from-custom-fonts/) where the font is downloaded asynchronously but not rendered to the screen until the second page visit.

// ** Pseudo Ruby **

// HEADER

if fonts_are_cached do

<link href="woff.css" rel="stylesheet" />

end

// FOOTER

if !fonts_are_cached do

<script>

// Load in custom fonts

$.ajax({

url: '#{asset_path("woff.css")}',

success: function () {

// Set cookie

}

});

</script>

end

A cookie is used to determine whether or not to render the stylesheet inline or load it asynchronously further down the page.

What I like about this solution is that it eliminates the requirement for managing FOUT and forces you to not treat your fallback fonts as second class citizens. The downside to this approach is users who bounce straight from your site will download an asset that is never used so this technique should be used dependant upon your user behaviour.

It does raise the interesting question of how important a web font really is though: if you're happy to serve the first view without one then is it really necessary at all?

The Future - Progressive Enhancement?

The issue of loading fonts really highlights the nuance of managing web performance. Rarely is there a holy grail solution to the problem; you need to balance the different performance costs and work out what is best for your user base. How much of your content is using fonts? How critical is that content? What’s the cost of a round trip?

In my opinion we need to stop thinking of web fonts as critical to the page and serve them only to users for whom it will enrich their experience. Making content unreadable for users on slow connections can't be the sacrifice for other users not seeing a repaint. In order to come up with a real solution we need to be able to differentiate between the two groups.

At EdgeConf earlier this year there was a discussion around whether or not having access to the connection speed of the user would be beneficial, misused or even necessary. What would you use it for?

It could certainly be valuable in this situation, allowing us to only load fonts when we feel it would be in the user's interest. Ideally this would not be a client-side solution.

If Client Hints were able to expose this information we could decide whether or not to include the font on the server side. Even better, we could send that font with a header which told the browser if the font should block the render or not. These are all wishful solutions though. In the meantime we may have to roughly determine the connection speed of the browser using timing APIs.

Progressive enhancement for web fonts does not need to be limited to performance issues either. There are other features we could be testing upon to determine whether or not to serve fonts: sub-pixel font rendering support, for example.

I would always favour a solution which leverages the browser where possible. Despite this, for the moment, if you want to control this part of your website's performance you are going to have to work around the browser. Hopefully in the future we will have the ability to make better judgements using native capabilities, in the meantime we need to take a more thoughtful approach to including fonts on our web pages.